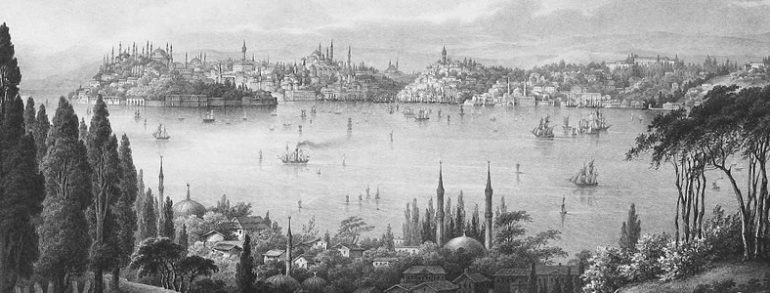

"Constantinople, Never. It is the Empire of the world," said Napoleon Bonaparte of France in late 18th century, when the Tsar Alexander of Russia constantly forced Napoleon to allow him to take Constantinople. Actually, Napoleon was not the first person with this thought. Millions have migrated here for thousands of years for the same bond to the city.

Prehistory

During the construction of a new metro station and the Marmaray tunnel at Yenikapi, located in the historical peninsula, the original Istanbul, 8500-year-old settlement dating to the Neolithic Age was unearthed. This discovery proved that the first settlements in the historical peninsula of Istanbul started much earlier. The end of the ice age and the development of the 32-km Bosphorus Straight was around 5300 BC.

The Byzantine Empire

The first settlers in the Propontis (the ancient name for the Sea of Marmara) were Megarians, who followed the Persian Megabazus and established their colony in 685 on the Asian side; since the European side did not look secure enough for them. They named their city Chalcedon, “the City of the Blind".

They waited for almost 17 years to gain strength before expanding their colony to the European side of the water. It is believed that, one of the early people who moved to Seraglio Point (today, Sarayburnu) was Megarian Byzas. The new city was established around 667 BC, and was called Byzantium. The area proved very productive for them. In addition to the farming in a mild weather condition, excellent fishing on the calm water made their transition into their new land easier.

Once being a part of the Delian League under the leadership of Athens, then Second Athenian Confederacy (378–355 BC), Byzantium finally gained its quasi-independence in 355 BC, almost three centuries after its foundation. The powerful figure in that era was the Alexander the Great (336–323 BC), the king of the Macedon Kingdom.

The Roman Period

Benefited from its alliance with Romans early on, Byzantium was an ally of the Romans, and developed into an independent city with its own culture, wealth and beauty. The relationship between the Romans and the Byzantines changed its course over the years, and the influence of the Romans over them gradually increased as time passed. The independent spirit of Byzantines eventually bothered the Romans. During the reign of Vespasian (69-79), Byzantium thereby lost its privileges and became a subject of the Roman Empire.

In 196, during the “Year of the Five Emperors”, a war brought Roman Emperor Septimius Severus (193-211) to Byzantium. As Byzantium supported his rival, Pescennius Niger (193-194), Severus had to take a position against the city-state. Byzantium surrendered after three years of siege in 196, but its surrender did not save it from being severely punished by Severus: Byzantium lost some of its rights as a subject. Severus razed the city, including the city walls.

Severus could not leave the city ruined; he rebuilt it. He also constructed the Hippodrome and expanded the city borders by building new walls, the Severan Walls. To honor his son, he named the city Augusta Antonina.

Around the 3rd or 4th century, the Column of the Goths was erected to commemorate the victory of the Romans against the Goths, an East Germanic tribe. It is one of the oldest remaining Roman monuments in Istanbul, now located in Gülhane Parkı next to the Topkapi Palace.

The Roman Empire

Constantine the Great (306-337) was the other Roman Emperor who noticed the strategic importance of Augusta Antonina. He thought Rome would not be a safe place for the Roman Empire anymore, and merging the western and the eastern territories was the best alternative for the empire to continue. Since Severus, the city had the infrastructure based on the Roman planning and urban designing. Therefore, he simply moved the capital 1,400 km east.

He transformed the city into a new capital of the Roman Empire in 330. In respect to the founding father, Constantine the Great, the name of the city was changed to Constantinople (City of Constantine). The name stayed as the official name of the city throughout the Byzantine period. It was also called “Nova Roma or Second Rome”. Rome and Istanbul had one thing in common; they both have seven hills. Istanbul’s seven hills are located on the historic peninsula. This gave Istanbul a nickname of "The City on Seven Hills".

Constantine built the Great Imperial Palace. The Forum of Constantine (today, Çemberlitaş Square), where the Column of Constantine is still standing. He expanded the official borders of the city beyond the Severan Walls. Therefore, he tore down the current walls and built new defensive walls, called the Walls of Constantine.

By being the first Christian Roman emperor, he removed penalties for being a Christian through the Edict of Milan, which gave religious freedom to his subjects. This changed the feature of the city. For the first time basilica churches erected. Istanbul is still rich with historical churches and monuments from this period, such as the Cistern of Philoxenos. He also renovated the Hippodrome. The Milion Stone, erected by Constantine, was a mile-marker monument similar to the Milliarium Aureum in Old Rome. The Serpent Column in the Hippodrome was also erected in his time.

The Valens Aqueduct, a major water-transportation system, was built during the reign of Emperor Valens (364-378).

The Eastern Roman Empire

It was the beginning of the reign of Arcadius (395-408) in 395 when Constantinople was permanently separated from Rome upon the will of his father Theodosius I (379-395), who built the Forum of Theodosius I, (today, Beyazıt Square). The Obelisk of Theodosius, which was originally dedicated to Tutmoses III (1479–1425 BC), the sixth Pharaoh of Egypt, was brought to Constantinople in 390 by Theodosius I. The Harbor of Theodosius I, which belonged to the early Byzantine period, was unearthed during the construction of the metro station and the Marmaray Tunnel Central Station at Yenikapi. The 35 ancient ships were among the findings of the excavation.

During the 42 years of reign of Theodosius II (408-450), Constantinople had major changes. The most important things were the fortification of the city in 413 by the land walls and in 439 by the Sea Walls, called Theodosius Walls, founding of the University of Constantinople (the first university in Europe), the compilation of the Theodosian Code (438) and the rebuilding of the great church of Hagia Sophia (415). The earthquake of 447 unified the whole city. It was so severe that not only the houses were destroyed, but also new walls including 57 of the 96 rampart towers were flattened. Everything negative happened at the same time. The earthquake was coincided with the advancement of Attila the Hun on Constantinople. The citizens did their best and restored the fallen walls in less than three months, also added the inner walls and the moat into the system. The area of Blachernae (today, Ayvansaray) in the northwest part of the city was not included in the official border of the city of Constantinople.

The Column of Marcian was dedicated to the Emperor Marcian (450-457) during his reign. The Monastery of Stoudios, founded during the reign of Leon I (457-474) in 462 by the consul Stoudios, was one of the most important monasteries of Constantinople. It is one of the oldest buildings of the Eastern Roman period in İstanbul.

The 28-year reign of Emperor Justinian I, (527-565) was one of the most important periods of Constantinople. He came to power when the state was decayed. Saint Sergius and Bacchus Church (Küçük Ayasofya Camii) (527-536) was built following the ascension of Justinian to the throne. Justinian married Theodore, a dancer.

Nika Riot in 532, a clash between the ruled and the ruler (or the fans of the two chariot teams of ‘Greens’ and ‘Blues’ and Justinian & Theodore), became the most violent riot in the history of Constantinople. Almost 30,000 rebels were slaughtered and half of the city was burned, including the Hagia Sophia and Hagia Irene. After the riot, Justinian redesigned the area of the Hippodrome, the Palace and the Forum of Constantine.

Justinian I rewrote the Roman civil law between 529 and 534, the Corpus Juris Civilis, the basis of the current civil law in many modern states. He rebuilt the great church of Hagia Sophia in 537, five years after its destruction in the Nika Riot.

Justinian also switched the dominant language in his administration from Latin to Greek.

In Justinian’s time, Constantinople faced one of the greatest plagues in history. The bubonic plague killed almost 50% of the 500,000-population of the city in 542. According to the historian Procopius, it was originated in Egypt and spread through Asia Minor (Anatolia) to Italy and Europe. He rebuilt Hagia Irene and constructed Basilica Cistern (548), an underground water storage. The severe earthquake in 557 damaged many buildings including the Church of Chora (Kariye Museum), but it was repaired.

Heraclius (610-641) introduced Greek as the Eastern Empire's official language. The city was besieged by the Avars in 626.

During the reign of Constantine IV (668-685), the city was besieged by the Arabs in 674-677. Among those killed during the siege was Eyüp Sultan (Abu Ayyub al-Ansari), the standard-bearer to the Prophet Muhammad. After the conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Turks in 1453, a tomb and a mosque were constructed for his honor.

The Second Arab Siege (717-718) was also a failure. With the help of Bulgars, Leo III (711-741) had overcome the siege successfully.

Kastellion of Galata, a part of Fort of Galata, was built in Galata (today, Karaköy) in the beginning of the 8th century to close off the Golden Horn. Now, it is used as a mosque, the Subterranean Mosque (Yeraltı Camii).

In terms of the religious icons and other symbols or monuments, the reign of Leo III (717-741) was a bad time for citizens, as it marked the beginning of the Iconoclastic Period (730–787) in Constantinople. Iconoclasts (in Greek, Icon-breaker) destroyed all the icons for religious or political motives, and replaced the images in churches with crosses. The church of Hagia Irene is the best example of the Iconoclastic Period. It was ended by the Second Council of Nicaea (today, Iznik) in 787.

The real construction date of the Walled Obelisk is unknown, but it was named after Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (913-959), who repaired it. The Column was once entirely covered with bronze relief plaques, which were stripped off by the Latin during the Fourth Crusade in 1204 and melted by them to mint coins.

The nickname for Istanbul “Queen of Cities” was created from the city's importance and wealth throughout the middle ages. The royal purple was the color of the Byzantine imperial family. The Byzantine emperors called themselves as "the Royal Purple Blooded”.

During the reign of Constantine IX Monomachos (1042-1055) in 1054, the great church of Hagia Sophia witnessed the Great Schism (East-West Schism), which caused centuries-long separation between the Western (Latin Rome) and the Eastern (Greek Constantinople) branches of Christianity. Both sides were militarily weakened by the repercussion of their decision.

In the Battle of Manzikert, the Great Seljuk Sultan Alp Arslan (1063-1072) defeated the Byzantine Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes (1068-1071). This war not only changed the political structure of the Middle East, but also prepared the collapse of the Byzantine power in eastern and central Anatolia.

Emperor Alexios I Komnenos (1081-1118) abandoned the Great Palace and moved the imperial residence to the suburban town of Blachernae. His mother-in-law rebuilt the Monastery of Chora, which is in close proximity with the new palace. During the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Chora also received its share of a wide range of destruction. The Anemas Dungeon (Anemas Zindanları) is a special structure built between the 14th and 15th towers of the Walls of Blachernae. It was constructed at the same time as the Walls by the emperor Alexios I Komnenos. This authentic middle age dungeon was named after its first inmate, Michael Anemas, who was a high ranked military officer of the emperor Komnenos. This chilling prison of Constantinople hosted many emperors and other well-known people.

The Byzantine-Venetian Treaty of 1082, signed between Alexios I Komnenos and the Republic of Venice, in the form of an imperial Chrysobull (Golden Bull, meaning Golden Seal), granted the Venetians extensive trading and tax-exemption privileges in the territory of the Byzantine Empire.

The Church of Pantokrator (Zeyrek Camii) reminds us of the impressive story of Piroska, the beautiful daughter of a Hungarian King. She lost her mother at two and her father at seven years old. At the age of 16, red-haired and orphaned Piroska, against her will, was sent to Constantinople by her cousin for a political marriage to John II Komnenos (1118-1143), the co-ruler of the Byzantine Empire. Piroska came to the city, where she did not know the language.

Empress Irene, her new name, wanted to build a church complex to help both local people and traveling Hungarians. The portrayal of Irene in mosaic was added on the church of Hagia Sophia together with her husband and her oldest son, Manuel I Komnenos. During the Latin invasion of 1204, the monastery was damaged and many of its relics and valuable assets were looted and taken to St. Mark's at Venice.

During the reign of Isaac II (1185-1195), the Byzantine-Venetian Treaty of 1187, in exchange for defense, restated exclusive social, commercial and financial privileges for the Venetians.

The Latin Empire

During the Fourth Crusade in 1204, originally intended to conquer Egypt. Venetians were asked to provide transportation across the Mediterranean. The cash-strapped Crusaders and power-hungry Venetians were pulled into Byzantium's internal dynastic affairs. Instead of Egypt, the Crusaders turned their siege upon Constantinople, and completely invaded the city on April 13 1204. The crusaders razed the city, destroyed the wealth of a millennium, a half of the city was burned, and valuables were all looted. Eventually, Constantinople turned to the days before the Romans. Venetians eventually received exceptional commercial privileges. The victory of the Fourth Crusade led to a new empire founded in Constantinople; the Latin Empire.

When it came to the partition of the Byzantine, Venetians grabbed the lion share, which gave them a strategic superiority against its rivals (mainly Genoese) in the region. However, the consequence of the rapid growth and expansion of the Republic of Venice was not free of cost. This dominating position bothered her enemies and created new jealousies among her rivals, especially Genoese and Ottoman Turks. Venetians had to cope with them alone. What is more, Venice, having a larger area to control, lost her flexibility.

The Revival of the Eastern Roman Empire

The commercial and military rivalry between Genoa and Venice played a big role in the Byzantine politics. Protecting its privileges in this extremely important commercial area became short-lived for the Venetians. Genoese, Venetians’ commercial archrival, waiting for an opportunity to get commercial privileges in Constantinople, signed a Treaty of Nymphaeum in March 1261 with Michael VIII Palaeologus, the Emperor of Nicaea, who wanted to take back Constantinople from the Latin.

Eventually, their alliance became the end of the Latin Empire. The Latin empire lasted over 57 years until Nicaean troops recaptured Constantinople on July 25, 1261. Michael VIII Palaeologus (1259-1282) became the new Byzantine Emperor. The Palaeologan dynasty ruled the Byzantine Empire for almost two centuries until the conquest of Constantinople in 1453.

As soon as he came to power, Michael VIII reestablished the Eastern Roman Empire in Constantinople. He reinstated all of the Byzantine culture and traditions, and tried to restore major public buildings damaged during the Latin invasion. In Genoese’s side, in exchange for a military support to Nicaea, they received tax and custom concessions throughout the Byzantine Empire, including establishing an independent commercial hub in Galata of Istanbul, on the other side of the Golden Horn across from Constantinople.

The area, known as "Galata" is the northern slope of the Golden Horn, now called Karaköy. This historic area was also called Pera, which means "Other Side" in Greek; "Pera en Sykaes" (the Fig Field on the Other Side).

Located in Blachernae (today, Ayvansaray in Fatih) the Palace of Porphyrogenitus (Tekfur Sarayı) served as one of the major imperial residences during the final centuries of the Byzantine Empire. The Latin word Porphyrogenitus means ‘born in the purple’. It is believed that the construction of the Palace of Porphyrogenitus started in the late 13th century. The Porphyrogenitus Palace was located at the north-end of the well-known Theodosian Land Walls.

The commercial and naval supremacy of Genoa, operating on the other side of the Golden Horn, Galata, fatally diminished the trading power of Constantinople. After the victory in the naval Battle of Meloria against Pisa in 1284, Genoese became the only dominant power in Galata. Even the Byzantines lost authority on the quarter.

The Church of Theotokos Pammakaristos (meaning ‘All-Blessed Mother of God’), consists of two buildings, was built by the nephew of Emperor Michael Palaeologus VIII between 1292 and 1294. After the conquest, this church had been used for patriarchate until 1586. Since then, the church has been used as a mosque (Fethiye Camii).

The Great Seljuk dynasty, dominated the region until 1307, was replaced by the Great Ottoman Empire, founded by Osman Gazi in north-western Anatolia in 1299. The Ottoman Turks became the next great challenge to Byzantium. Orhan Gazi (1281, 1326-1359), the second Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, captured Bursa, an important city in western Anatolia, where Byzantines also lost control.

One of the worst epidemic diseases in the world was the Black Death (bubonic plague) of 1347-1350. Genoese merchants not only carried commercial products between the ports, but also transported the deadly diseases from Kaffa (today, Crimea) first to Constantinople, then to Europe. The city lost a significant percent of its citizens in this tragic event. It is believed that about one third of the population of Europe died during the epidemic of 1346–1353.

Genoese Palace (Palazzo del Comune), built in 1316, still remains today in ruins on the Bankalar Caddesi (Avenue of Banks) in Galata. The Catholic Church of St Paul and Dominic (San Paolo e Domenico) was built between the years of 1323-1337. The church was converted into a mosque in 1475, and changed its name to the Arap Mosque.

The Black Death of 1347 not only destroyed the people, and but also undermined the already weak economy in Constantinople. Additionally, the Genoese, located in the Galata Quarter just north of the Golden Horn, eventually monopolized the trade rout on the Bosphorus, and established a customhouse, which collected commercial tolls from all ships sailing into the Black Sea, including Venetian and even Byzantine ships. The Genoese disregarded the Byzantine’s objections, and extended the granted area in Galata, surrounding it with 3-km Galata Walls. On the highest point of the citadel in the north, they erected the "Tower of Christ" (today, Galata Tower) in 1348 to watch Constantinople from above its Sea Walls and the entrance of the Bosphorus. The colony of the Republic of Genoa enjoyed its privilege in Galata even after the conquest of Constantinople.

In preparations for the Ottoman siege of Constantinople, planned to be in 1397, Sultan Bayezid I (1389-1402) built the Anatolian Fortress (Anadolu Hisarı) in early 1390s on the narrowest point of the Bosphorus on the Asian side. However, his defeat to Timur in the Battle of Ankara in 1402 forced him to abandon the siege.

In the last years of Constantinople before the conquest, the city was almost imprisoned within its defensive walls, and the population of the city fell to between 40,000 and 60,000.

The Conquest of Constantinople

The 21-year-old Mehmed II (1432, 1444-46, 1451-81), the seventh Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, made the final preparations to capture Constantinople. Speaking Greek, Latin, Serbian, Arabic, Persian, and Turkish, the well-educated Sultan was a true Renaissance intellect and international leader. He was taught one-on-one by the best teachers and thinkers of his time.

Between 1451 and 1452, Sultan Mehmet II built Rumeli Fortress (Rumeli Hisarı) on the European side of the Bosphorus, just the opposite side of the Anatolian Fortress. In order to obtain absolute control over the sea traffic of the Bosporus, the fortress was vital to prevent any help for Byzantines, coming from the Black Sea. During these years, Sultan Mehmed II also reinforced the Anatolian Fortress. Constantinople’s connections to the outside world by land was already fully cut off by the Ottomans.

The formidable Theodosius Walls, consisting of an inner wall, an outer wall and a moat, was the strongest defensive system in the world. The Latins of the Fourth Crusade passed it through its Sea Wall from the Golden Horn in 1204. Mehmed II targeted to enter the city through the Land Walls in the west. He needed a special cannon to penetrate the wall. Therefore, he used the 17-ton Şâhi Cannon, the most impressive artillery of all time, and the largest gun ever made. He planned to make a significant damage to the Wall from above the ground as well as under the ground. Thus, he employed the best tunnel constructors (Lağımcılar) from both his army and Serbia. He also compiled an army of 70,000. It was a sizable army compared to the Byzantine army of 10,000. Emperor Constantine XI (1405, 1449-1453) did not accept Mehmet II's offer to surrender the city, but bravely defended his city and heroically died on the last day of the siege. He was a true captain of his boat.

The 21-year-old Mehmed II successfully reached his goal after 53 days of siege, and entered the city on May 29, 1453. He received his honorary title of "the Conqueror" (in Turkish, Fatih). As he wanted the city to be the capital of the Ottoman Empire, he let his army loot the city only one and a half days, instead of the traditional three days when cities do not surrender. He calmed the citizens of Constantinople and told them to return to their homes safely and to continue their daily routines. He renovated the Theodosius Walls and aqueducts. Most importantly, he freed all the slaves.

The conquest of Constantinople by the Ottoman Empire opened a new chapter in the history of Europe, and officially marked the end of the Roman and Byzantine Empire, which had lasted for nearly 1,500 years.

The Ottoman Empire

The last Emperor Constantine XI did not have any children, but his brother, Theodore, had three children. Mehmed II appointed them high-ranking positions in his administration. He instituted a brand new rules and laws necessary for the foundation of the empire. This was essential for the multi-language, multi-religion, and multi-ethnic Eurasian empire. He also installed Gennadius Scolarious as the Patriarch of Constantinople.

Mehmed II converted the great church of Hagia Sophia into a mosque, and created a new mosque complex by adding other functional facilities to the mosque. He built the Eyüp Sultan Mosque and a tomb to honor Ayoub al-Ansari, the standard-bearer and close friend of the Prophet Mohammed. Eyüp died during an Arab siege of Constantinople in the late 7th century. The tomb, one of the holy sites for Muslims, preserves some of the personal belongings of Prophet Muhammad. The mosque was rebuilt by Sultan Selim III in 1800.

The young and skilled Sultan rejuvenated the economic life and reinstalled the city's "commercial center" identity. He established new specialized market places; one of them was the Grand Bazaar, built in 1461. He also built in 1470 the Fatih Mosque Complex (külliye), which was the first külliye with its high-domed mosque, university (the Eight Auditorium) and other functional buildings laid out symmetrically.

Mehmed II built his own palace in the neighborhood of Beyazit, currently occupied by the Istanbul University. However, due to security reasons, the palace did not serve his purpose, but it stayed as a royal residence until the mid-16th century. He built the "New Palace", called Topkapi Place in 1478 in Sarayburnu (cape of the palace) on the first hill by the Sea of Marmara. The area, which overlooks the city, was behind the walls and well protected. He afterwards permanently moved the capital of the empire from Edirne to Istanbul. At the end of his reign, the population of the city increased to over 100,000.

Like the second Theodosius of the Byzantine Empire (401-450), the builder of the Theodosian Walls, the second Mehmed of the Ottoman Empire (1432-1481), the conqueror of the Constantinople, died at the same age of 49, almost a thousand years later.

During the reign of the Ottomans, the name “Constantinople” was used by the Westerners when they referred to the metropolitan city of Istanbul (including Galata, Üsküdar). Ottomans used the same name, but with a different spelling, ”Konstantiniyye”. When they only referred to the walled city (historical peninsula), the Europeans used to say “Stamboul”, but the Ottomans called it “Istanbul”. The Ottomans also used the metaphorical name of “Dersaadet” (Gate of Felicity) for Istanbul.

Ottoman Empire brought Turkic-speaking Karaites (or Qaray, and Karay in Turkish) from Crimea to Galata. They were originally Turkic people who accepted Judaism. Galata was then referred as the “Qaray village”, or "Karay Köy" in Turkish. In time, the name of the region became "Karaköy".

During the reigns of the following sultans after Mehmed II, Constantinople’s rich collection of the monuments in Roman and Byzantine architectural styles became richer with the addition of the new structures in Ottoman architectural style with Byzantine and Seljuk features.

The Ottoman Sultan Bayezid II (1448, 1481-1512) invited the Jewish people who were expelled from the Iberian Peninsula during the Spanish inquisition in 1492, as they were forced to convert to Christianity or flee their homes. The first group was from Spain and a couple of years later from Portuguese. Bayezid II settled them on the north shore of the Golden Horn. They were called Sephardic Jews (or Spanish Jews), who spoke Spanish (Castellano), called Ladino, which is derived mainly from old Spanish, with many influence from Turkish, French and some Hebrew. Zulfaris Synagogue, built in 1823, was converted into a museum in 1992 to celebrate the 500th anniversary of immigration of the Jews to Istanbul.

The Marmara Sea earthquake, happened on the night of 10 September 1509 without foreshock, caused huge damage to the city. The estimated population was around 160,000 in Istanbul, and 35,000 in Galata. The earthquake killed over 4,000 people, and left almost every house, including the Theodosian Walls damaged.

The age of Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (1494, 1520-1566) became the richest period of the Ottoman Empire. They employed the best people and used the best materials to build lavish structures. Sinan the Architect (1489-1588) was one of them. The prominent architect put his signature on many famous buildings and complexes during his long life. Ibrahim Pasha Palace, renovated by Sinan in 1520 and given to Ibrahim Pasha, was one of the Grand Viziers of Sultan Süleyman I. The building now hosts the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum, which displays an extensive collection of religious and other Turkish treasures dating from the 8th Century. Süleymaniye Mosque Complex, built in 1557, was one of Sinan’s most important structures. The complex became the biggest supporter of the social and cultural life in the neighborhood. The Rüstem Paşa Mosque, commissioned to Sinan, was built in 1561 by Rüstem Paşa, who was one of the Grand Viziers of Sultan Süleyman I and married to Mihrimah Sultan, the daughter of Sultan Süleyman.

In the following centuries, we see fewer complexes. One of them is the Sultanahmet Camii, commissioned to the architect Sedefkâr Mehmed Agha, and built in 1617. The construction of the Yeni Cami Complex with Egyptian Bazaar was started by Safiye Sultan in 1597, but her half-finished complex was completed by Valide Turhan Sultan in 1663.

The great fire in July 1660 destroyed a minimum of a third of the historic peninsula within two days. It was the worst fire the city had ever experienced. Thousands also died from epidemic diseases after the fire. The fire around Eminönü in 1688 also destroyed around 1,500 houses and 5,000 stores. The Egyptian Bazaar was burned down in 1691. Thousands of lives and buildings were again destroyed by the three different fires in 1693. The fire in 1701 significantly damaged the Grand Bazaar. One of the worst fires broke out in 1729 and burned down one out of every eight buildings.

After costly experiences in the past century, the Fire Department of Istanbul (Tulumbacı Ocağı) was established within the janissary (professional army) organization in 1717 during the reign of Ahmed III (1673-1736). He was the sultan of the Tulip Age in Istanbul. The beautiful Fountain of Ahmed III in front of the Topkapi Palace was built in 1728. Aynalıkavak Pavilion, built by the same sultan now hosts the Music Museum, which contains 65 musical instrument and other music related objects.

The earthquake, occurred in May 1766, damaged many public and private buildings, and caused the loss of 5,000 lives. Among the damaged buildings was the Fatih Mosque, whose dome and walls collapsed. The current mosque was constructed between 1767 and 1771. The earthquake also destroyed the Eyüp Sultan Mosque.

With Sultan Mahmud II (1785, 1808-1839), the Ottomans started to modernize the empire. He was the first Sultan portrayed in the official portraits as a modern man, instead of dressing in traditional Ottoman garb. He believed that in order to modernize the army, reforms should also be made in the non-military institutions. Therefore, he opened the first medical school, military academy, and established the secondary school system. The most significant reform he achieved was the demolition of the old janissary (military) organization, and established a modern army on 16 June 1826, historically named Vaka-i Hayriye (Fortunate Event- Hayırlı Olay).

Period of Reformations

The political system of the Ottoman Empire was reorganized by a letter presented to the public in Gülhane Park of the Topkapi Palace on 3 November 1839, four months after Mahmud II died. Therefore, Mahmud II became the last Ottoman sultan who had ultimate power without any limitations.

In order to improve the social life by integrating minorities in the society, improving equality, and improving the efficiency of the bureaucracy, the Imperial Rescript (Tanzimât Mektubu) efforts were led by Mustafa Reşit Pasha, the Foreign Minister. The succeeding sultan, Abdülmecid (1823, 1839-1861), signed the edict, and abided by the terms throughout his reign. Five years after the “Tanzimât Era” in 1844, the current Turkish Flag was formed and the eight-pointed white star on the red background was changed to five points.

This was the period of a construction boom. Sultan Abdülmecid was affected by his contemporaries too. He built the Dolmabahçe Palace in 1856 on the “filled-in garden” of the Bosphorus, designed by Garabet and Nigoğos Balyan in the mixed architectural styles of Ottoman, Baroque, Rococo, and Neo-classic. Bezm-î Alem Valide Sultan, Abdülmecid’s mother, built the Galata Bridge in 1845.

The three-year Crimean War (1853-1856) between the Russians and the allies of the British, French, Sardinians and Ottomans marked the beginning of the Ottoman’s first public indebtedness. The Empire deeply suffered from this financial crisis in the following long decades. The improvements established by the edict of Tanzimât, aiming to put Muslims and non-Muslims on equal standing, was expanded again by the Reform Decree (Islahat Fermanı) on 18 February 1856 by Abdülmecid.

The famous English nurse, Florence Nightingale (1820-1910), dubbed "The Lady with the Lamp", was invited to Istanbul to help the wounded British soldiers in Crimea.

Also called Mecidiye Pavilion, Beykoz Pavilion located on the Bosphorus was completed in 1854 by the son of Mehmet Ali Paşa, and given to Sultan Abdülmecid as a present. Designed by Garabet Amira Balyan and Nigoğos Balyan in Neo Baroque style, the picturesque Ortaköy Mosque was built in 1856 by Sultan Abdülmecid. Küçüksu Pavilion, another small palace used for hunting, situated on the Bosphorus, was built by Sultan Abdulmecid in 1857. That same year he also had the Leander’s Tower (Maiden's Tower or Kız Kulesi) rebuilt, located on a tiny island in the Bosphorus.

Inspired by his travels to Egypt and Europe, Sultan Abdülaziz (1830, 1861-1876) started building two palaces in 1863 on both sides of the Bosphorus. The Beylerbeyi Palace, designed by Sarkis Balyan in French neo-baroque style with a traditional Ottoman plan, was completed in 1865 and the Çırağan Palace, designed by Sarkis Balyan in North African Islamic architectural style, was completed in 1871.

The Church of St. Mary of Blachernae was reconstructed in 1867 on its original site. The original church was burnt down in 1070, occupied by Catholic Latins during the Fourth Crusade, and was destroyed again by fire in 1434. The church is famous for its Hagiasma (fountain of holy water), Hagion Lousma (sacred bath), and the 7th-century icon of Theotokos of Blachernae, (Our Lady of Blachernae).

First and Second Constitutions in 1876 and 1908

Internal and external factors pressured the empire to reorganize itself. It was then believed that the best strategy for the Empire was to change the political system to “constitutional monarchy”. For this transition, Sultan Abdülaziz (1830, 1861-1876) was dethroned on 30 May 1876 and Murad V became sultan the same day, but his reign lasted only three months. 34-year-old Abdülhamid II became the 34th sultan of the Ottoman Empire, and the first constitution and parliament (Meclis-i Mebûsân) was introduced on 23 December 1876. This ended the period of reformation (Tanzimât Era), 37 years after it started in 1839. Many reasons, unfortunately, forced Abdülhamid II to abolish the parliament right after its first meeting.

Abdülhamid II (1842, 1876-1909, 1918) was well educated and had an excellent memory. He learned economics, finance, history, diplomacy and even invested in equities on his own. He traveled to Egypt and visited London, Paris and Vienna with his uncle, Sultan Abdülaziz. His wit and talent contributed to his remaining in the power for 33 years.

The wide-open Dolmabahçe Palace on the shore of the Bosphorus did not fit the traditional Ottoman palace system of walled-courts, like the one in Topkapi. Abdülhamid II, therefore, moved the empire from Dolmabahçe Palace to the Yıldız Palace within the first year of his reign, in 1877. More structures were gradually added to the palace, so that a palace complex in Yıldız was eventually created. He stayed distant from the public. Apart from his visits outside in religiously important days, he never appeared in public. Therefore, the Yıldız Palace fit his personality and governing style.

In the following year of his enthronement, Abdülhamid II found himself in the middle of the Turkish-Russian War of 1877-1878. After the war, not only did he lose a big piece of land, but he also lost so much money that the debt burden of the treasury reached an astronomical level, which ended with a moratorium. To guarantee the repayments of the foreign debt, the tax revenues of the six major domestic products were left to the control of the "Ottoman Public Debt Administration" (Düyun-u Umumiyye) (1881-1939), managed by the representatives of the lending countries.

Galata quarter, the largest and best-known Italian trading base and the 13th Region of Constantinople, was famous for its private commercial status. It continued to be an opening gate to the outside world even after the conquest in 1453, and continued to be a commercial center for Italian, French, German and Armenian, Jewish and other European merchants. After the 19th century, this area became a hub for business, shipping, and banking. As the Empire’s economy grew over the centuries, the commercial area in Galata expanded toward the north.

In the middle of the 19th century, Istanbul needed road expansions, street lightings, sidewalks, and improvement of building methods. The government then formed a Commission for the Order of the City in June 1858. The commission created fourteen districts in the city. The Sixth District of the municipality, covering the area of Pera, Galata and Tophane, was chosen as a special zone, and responsibility of the sixth district was given to the local businessmen, who also financed their projects. They dismantled most of the original Galata walls around the late 1860s. The construction of the İstiklal Avenue (Rue de Pera) started then. Beyoğlu, which was then the area above Galata, where the Venetian embassy was located, took the name from the Venetian word “Bailo”, (ambassador).

The late 19th century Art Nouveau Camondo Steps are currently decorative components of the Bankalar Caddesi of Galata with Camondo's impressive history of almost 150 years. Those steps well represent the rise and fall of the Camondo dynasty, the Rothschilds of the East.

The Sirkeci Train Station, mentioned as the last station in the worldwide known novel, the Orient Express by Agatha Christie, was completed in 1890. The Istanbul Archeological Museums, to display the rich collection of 1 million ancient objects, were created by Osman Hamdi Bey and opened to the public in 1891. The displayed items belonged to the civilizations from North Africa to the Middle East including Mesopotamia as well as the Balkans and a wealth of artifacts from the 100 centuries of Anatolia’s history.

The Bulgarian St Stephen Church, built in 1898, is also known as "the Bulgarian Iron Church", which is famous for being one of the world’s last surviving pre-fabricated cast iron churches.

The Neo-Renaissance style Fountain of Wilhelm II was a present from the German emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II to Abdülhamid II. It was produced in Germany and brought to Istanbul in pieces, and assembled in the Hippodrome in 1901.

The end of the 19th century marked the Young Turk Revolution, and serious events lead to the end of the Ottoman Empire. At the end of the reign of Sultan Abdülhamid II, the Second Constitution was introduced and the parliament was reopened on 24 July 1908, 32 years after the first constitution. This ended the Ottoman sultans having full imperial power and a title of Caliph. Abdülhamid II was the last sultan with that power, and the subsequent sultans shared their authority with the parliament. The political system of the Ottoman Empire permanently changed to a “constitutional monarchy”.

The Haydarpaşa Train Station with a unique feature for a railway station was built in 1909 on the land reclaimed from the sea. Therefore, it is surrounded by water on three sides.

In the very beginning of the 20th century, almost 40 languages were spoken in the Galata area. It became such a multi-lingual district that those people combined several languages in one sentence, similar to the Spanglish (the combination of Spanish and English), but not limited with two languages. It was then a popular saying;

“In Pera, there are three misfortunes: plague, fire, and dragomans (interpreters)”.

Republic of Turkey in 1923

After the World War I, Istanbul was shortly occupied by the British, French and Italian troops, which ended with the Treaty of Lausanne in 24 July 1923.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Republic of Turkey, declared the establishment of the independent Republic of Turkey in 29 October 1923. He moved the capital to Ankara, and Istanbul stayed as the commercial center of the country.

A. Ihsan Toksü

A. J. Graham, (2006), “37 - The colonial expansion of Greece pp. 83-162), The Cambridge Ancient History, Volume III, Chapter 37, Second Edition, Seventh Printing, Cambridge University Press, p.120

Alexander A. Vasiliev, (1952) “History of the Byzantine empire”, Blackwell, pp.550-552

Abdülkadir Gündüz, (2013), “Is Turkey an Earthquake Country”, The Journal of Academic Emergency Medicine, Volume:12, Issue:1, Mar 2013

Andrew Louth, (2008), “Justinian and His Legacy (500–600), The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c.500–1492”, p.122.

Andrew Louth, (2008), “Byzantium Transforming (600–700), The Cambridge History of the Byzantine Empire c.500–1492”, Chapter.4 Cambridge University Press, p.228

Brian Campbel, (2005), (1 - The Severan Dynasty, the Crisis of Empire AD 193-337, the Cambridge Ancient History” Volume 12, 2nd Edition, pp. 3-4

Canan Parla, “Türkiye’nin kültürel mirası-I” Anadolu Üniversitesi, p.23

Doğan Kuban, (1969), “İstanbul'un Tarihî Yapısı”, p31

Edhem Eldem (2009), “Istanbul, Encyclopedia of the Ottoman Empire”, Gabor Agoston and Bruce Masters, pp.286-290

Edwin A.Grosvenor (1900), “Constantinople”, Volume;1, Little, Brown, & Co., Boston, pp:24-25

Erhan Afyoncu, (2013), “Osmanli Tarihi (1566-1789)”, Anadolu Universitesi, pp.87, 116, 119-120, 139, 159

Gisele Marien, (2009), “The Black Death in Early Ottoman Territories, 1347-1550", Master of Arts, Bilkent University, Ankara

http://www.istanbularkeoloji.gov.tr/web/41-225-1-1/muze_-_tr/muze/kazilar/yenikapi_kazilari

J.B. Bury, (1923), “Later Roman Empire from Theodosius I to Justinian”, V.1, pp.86

J.B. Bury, (1923), “Later Roman Empire from Theodosius I to Justinian”, V.1, pp.43

John Atkinson, “Getting to know Justinian”, University of Cape Town.

Lowry, Heath W., (2003), "The Nature of the Early Ottoman State", SUNY Press,

Mehmet Ali Kaya, “Roma İmparatoru Septimius Severus Doneminde Anadolu”, p.39

N.N. Ambraseys and C.F. Finkel, (1990) “The Marmara Sea Earthquake of 1509”, Terra Nova, Volume 2, Issue 2, pp 167-173

Namik Erkal, (2011) “The Corner of the Horn: an Architectural Rivew of the Leaded Magazine in Galata, Istanbul”, METU

Ole J. Benedictow, (2004), “The Black Death, 13461353: The complete history”, The Boydell Press, Woodbridge, UK.

Reşat Ekrem Koçu, “Tulumbacilar” http://www.ibb.gov.tr/sites/itfaiye/workarea/Pages/tulumbacilar.aspx

Robin Seager, “The King's Peace and the Second Athenian Confederacy”, the Cambridge Ancient History, Volume VI, Fifth printing 2006, Chapter.6, p.166

Rosemary Horrox, “The Black Death”, Manchester University Press, Manchester & New York, p.9

Stanford Shaw, (1997), “Conquest of a New Empire: The Reign of Mehmet II, 1451-1481, the Apogee of Ottoman Power, 1451-1566”, History of the Ottoman Empire and Modern Turkey. Cambridge University Press, p.59

Stefen Turnbull, (2004), “The Walls of Constantinople AD 324-1453”, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, United Kingdom, p.7

Şevket Dönmez, (2003), (Yeni Arkeolojik Araştırmalar Işığında İstanbul’un (Tarihi Yarımada) Neolitik, Kalkolitik ve Demir Çağı Kültürleri Üzerine Genel Değerlendirmeler”, Vakıf Restorasyon Yıllığı 2. Restorasyon, Konservasyon, Arkeoloji, Sanat, İstanbul: 19-25.