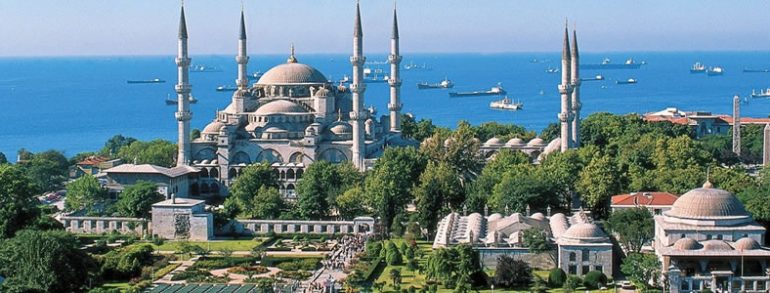

Sultanahmet Camii Külliyesi (1609-1620)

If the armies of the Fourth Crusade had not razed Constantinople in 1204, we would have enjoyed visiting the Palace of Daphne, the oldest part of the gorgeous Great Palace of Constantinople. However, now, thanks to Sultan Ahmed (1603-1617), we have another magnificent monument, built almost four centuries after the fourth Crusade.

The Blue Mosque Complex (Sultan Ahmed Külliyesi), a major element of the silhouette of Istanbul, is one of the last samples of the Classical Ottoman architectural heritage.

Ahmed desired very much to build an imperial (selâtin) mosque to symbolize his piety. The mosque was built to equal his great belief in Islam. Since the construction of the Süleymaniye Mosque, built by Sultan Süleyman the Magnificent (1520-1566) in 1557, none of the sultans started and completed any imperial mosque (selâtin cami). Ahmed wanted to be the first sultan since then.

Many people in his circle objected to the idea of a new imperial mosque. In the Ottoman tradition, building an imperial mosque (selâtin cami) had to be related to specific conditions, such as the Empire having captured an important land or having won a lucrative war and thus receiving significant war gains from the defeated enemy. Unfortunately, the empire had financial problems in those years. The Empire could not afford to spend such money for a significant project.

Ahmed, referencing his defeat of the Celali Rebels in Anatolia, claimed that he deserved the mosque. He also paid for the cost of the mosque out of his own pocket. Ahmed eventually convinced them, as he needed a monumental symbol of his power and piety. Thus, he started planning his signature project, the Blue Mosque. Ahmed had to figure out two matters; finding an architect, and a location for the large complex. Ahmed appointed Sedefkâr Mehmet Agha as chief architect and Kalendar Pasha as his finance director to supervise the project in 1606, and ordered them to start the mosque project as soon as possible.

Finding a large land necessary for this major project became a big hurdle as the historical peninsula was already fully occupied. On the other hand, an imperial mosque of this size should be erected in one of the most important areas of town. With this goal in mind, they decided on the land, which was on the south side of the church of Hagia Sophia, and next to the Hippodrome of Constantinople. This land with a view of the Marmara Sea and the Anatolian side of Istanbul is located on the dominating first hill, also housing the Topkapi Palace.

The first structure on the land was the Great Palace of the Constantinople. As the Byzantine palace was destroyed by the Latin invaders during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the imperial palace was moved to Blachernae (today, Ayvansaray). During the Byzantine period, the columns and other important components of the ruined Great Palace were already re-used in other structures. It was a common practice in those years, called spolia in Latin, to re-use former building’s decorative or structural materials in new buildings. For instance, the decorative marble columns of the Hagia Sophia, under Justinian's orders, were brought from the ancient buildings in the other ancient cities, as was the case with the Basilica Cistern. Therefore, some parts of the construction area of Sultanahmet had been filled with the ruins of the Daphne Palace, one of the major wings of the Great Palace of Constantinople.

Additionally, they needed a sizable area to build a very large complex. Therefore, the land that belonged to the Ismihan (Esmehan) Sultan and Sokollu Complex built in 1571 by Sinan the Architect was purchased. This acquisition made it possible them to expand the Land toward the curved side of the Hippodrome, called Sphendone.

After visiting many important mosques, churches and other famous monuments, Sedefkâr created the design fitting to the expectation of Sultan Ahmed. From land arrangement to financing, preconstruction preparations were completed by 1609, and the construction of the Blue Mosque started right away.

The mosque, made of brick and stone, has a splendid curvaceous exterior with a cascade of domes, and six fluted minarets. Its interior, based on the quatrefoil plan, was decorated by the charming blue Iznik tiles, which give the building the name Blue Mosque.

The construction of the Sultanahmet Mosque, also known as the Blue Mosque, was completed on 9 June 1617. Sultan Ahmed I and his circle happily prayed in the brand new imperial mosque. Unfortunately, his happiness was short lived. On 22 November 1617, five months after the completion of the mosque, Sultan Ahmed I passed away in Istanbul. He was 27 then. He could not pray there again, but his funeral was held there.

The year 1617, when the mosque was completed, turned out to be a sad year. Sedefkâr Mehmet Agha, the architect of the mosque, also died about the same time as Ahmed I. Their lives were tied to this structure.

For the following 250 years, most Ottoman sultans performed their Friday prayers at this mosque. Now, millions are visiting this mosque every year.

The area of the complex, known as the Hippodrome in Byzantine period, was called the Horse Square. Today, it is called Sultanahmet Square.

Other Structures of the Complex

After the completion of the mosque, it took another three years to complete the construction of the whole complex (Külliye) in 1620.

In Seljuk and Ottoman tradition, big charities, such as sizable mosques and hospitals, are formed under the structure of the charitable foundations, the vakıfs (waqfs), which were well-organized and specialized institutions producing revenue to use for the maintenance of the complex. Ahmed I established a vakıf (foundation) for his mosque too. His well-planned and rich foundation included many revenue-producing other businesses, which helped the mosque to stay in tack for centuries through present day.

The structures of the complex, built in harmony with the urban architecture, are not symmetrically situated around the mosque. Based on the land, Sedefkâr Mehmet Agha generously allocated the usable area to the mosque, and Byzantine monuments prevented him from expanding the area toward the Hippodrome. Therefore, some structures of the complex were place in the south side of the Hippodrome, called Sphendone.

The Complex included a religious school (medrese), a royal pavilion (hünkar kasrı), a shop-lined street (arasta), an elementary school (sıbyan mektebi), a building for Koran readers (darülkurra), a mausoleum (türbe), fountains and kiosks free drinking water and sherbet (sebils).

Unfortunately, some of the structures, such as the public kitchen (imaret-tabhane), the hospital (darüşşifa), the public bath, and kiosks, have not survived, neither have the lodgings, houses and cellars.

Most of the complex’ fountains still exist. The Public Bath (Sultanahmet Hamami), located on the southwest of the Arasta Bazaar, was damaged in the fire of 1912, It is currently not in good condition. The small single-domed building behind the mausoleum was a school for Koran readers called Darülkurra. Built in a square plan in 1620, today it is used as storage for the mausoleum. Only a few sections of the imaret (soup kitchen) and Darüşşifa (hospital) remain at the west side of the Hippodrome today. They were built in 1620 during the reign of Sultan Osman II (1618-1622).

Primary structures of the Blue Mosque complex include:

Sultanahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque)

Arasta Bazaar (Market Street) - Arasta (Sipahi) Çarşisi,

Hünkar Pavilion (Hünkar Kasri) - Vakiflar Carpet and Kilim Museum,

Mausoleum of Sultan Ahmet I (Türbe),

Sıbyan Mektebi (Ottoman elementary-primary school),

Medrese (Religious School) - Sultanahmet Medresesi

A. G. Paspates (1893) “The Great Palace of Constantinople” p,227

Ahmet Vefa Çobanoğlu, (2009), “Sultanahmet Camii ve Külliyesi”, TDV Isam Ansiklopedisi. Cilt.37, p.497

Godfrey Goodwin, (2003), “A History of Ottoman Architecture”, Thames & Hudson Ltd London, pp342-343.

Tulay Artan, (2006), “The Cambridge History of Turkey, 19 - Arts and architecture”, Cambridge University Press, pp. 408-480

Location: The Sultanahmet (Blue) Mosque Complex is located in the Sultanahmet neighborhood of the Fatih district in Istanbul, next to the Hagia Sophia.

Admission: Free. Donations are accepted.

Hours: This is a functioning mosque, therefore visiting hours are from 9:00 am to 6:00 pm every day, but visiting is interrupted during the prayer times.

Rules: when entering a Mosque, visitors are asked to take their shoes off and female visitors to cover their head and shoulders. Skirts and pants should reach below the knee. If needed, mosque officials will assist you. If there are signs, such as clearly prohibiting the use of flashes to protect the artwork, please, follow the rules.

Attractions Nearby: Hagia Sophia, Topkapi Palace, Hagia Irene, Grand Bazaar, Million Stone, Basilica Cistern, Hippodrome, Istanbul Archaeological Museums, the Turkish Islamic Arts Museum and Gülhane Park.

Sultanahmed Mosque (Blue Mosque)

Sultanahmet Camii (1609-1617)

The Blue Mosque, one of the main components of Istanbul's famous skyline, is the creation of the Sultan Ahmed I (1590, 1618-1622) and the Architect Sedefkâr Mehmed Aga (1540-1618), a student of Sinan the Architect. The 400-year-old structure is the last great mosqueof the classical age. Yeni Valide Mosque was built 46 years later in 1663, but it was based on the original plan of architect Davud Aga in 1597.

It consists of a main building and a courtyard on the north side within a walled enclosure with five gates. Bordered by a peristyle of 26 columns covered by 30 small domes, the marble-floored courtyard is as large in area as the mosque itself, and it was entered by three monumental bronze doors. The main entrance decorated with muqarnas is located on the Hippodrome side.

At the center of the courtyard is a hexagonal ablution fountain, decorated with the tulip and carnation motifs, but it is no longer in use. The functioning ablution fountains are located at the ground level of the northern facade. The glamorous domes of the mosque cascading with a pyramidal appearance impressively welcomes visitors from the courtyard. The perfect proportions and harmony of the exterior is easily noticeable.

The minarets are designed in the classic example of the Ottoman architectural style. The mosque has six minarets, which is the first in Turkey. The fluted minarets stand on the square base. Four minarets with three şerefes (balcony) are situated on the corners of the mosque and two of them with two şerefes on the north-end of the courtyard. All of these sixteen şerefes with muqarnas underneath has their own spiral stairways. We do not know if the number sixteen had a special meaning for Ahmed.

The tops of the domes and minarets are covered with lead. The crescents and the stars on them are made of gold-plated copper.

Upon entering the prayer hall through any of its three gates, a fascinating blue theme of fine handmade Iznik and Kütahya tiles and stained glasses captivate your attention. This dominant theme of blue actually gave the mosque the nickname “Blue Mosque”. Top quality ceramic tiles were produced in the cities of Iznik and Kütahya, when these cities produced their highest quality tiles. There are approximately 21,000 tiles with more than 50 different compositions inspired by floral patterns used below the third tier of windows. The finest tiles are placed on the north wall. Red and blue colored paintwork is used to decorate the areas above the tiles and inside of the domes. The other important component of these walls is the 260 stained glass windows situated on six levels from the floor to the dome. Plentiful light also helps highlight the tiles and the paintwork.

The tablets with the names of the caliphs and verses from the Koran were the original work of Kasım Gubari, the famous calligrapher of the time. The great Arabic calligraphies can never be seen anywhere else.

The 2,652 m² (51m x 52m) of interior is based on the quatrefoil plan. The center dome with the diameter of 23.5m and the height of 43m is expanded by four half domes. Each half dome is also expanded by three smaller semi-domes. The descending three tiered domes form pyramidal design, which can be viewed from the exterior. The center dome is supported by four colossal columns (elephant feet), each of which has a diameter of 5m.

Due to its special function, the qibla wall in the south side has different designs than the other walls. The mihrab niche with muqarnas in a tall marble frame, located just across from the main entrance, is positioned at the center of the qibla wall. The qibla is situated in the direction of Mecca, toward which the faithful must face while praying salah. In Turkey, the qibla is southeast. Above the mihrab, there are two verses from the Koran. To the right of the mihrab is the slim minber (pulpit), which looks like a staircase. On Fridays and Muslim holidays, the imam delivers his sermon to the congregation there. The finely carved marble minber has fine geometric patterns on the sides. The mihrab and minber were made of white marble brought from Marmara Island known for centuries for their high quality. Müezzin's Platform, situated behind the south-west column, is a lofty place on which müezzin stands up and repeats the call to prayer for the congregation to start the salah.

Situated on the left corner of the qibla wall is the hünkâr mahfili (royal lodge), which is solely reserved for the sultan himself and his guests to give them security and privacy in the mosque. The hünkâr mahfili, sits on ten valuable marble columns, has a richly decorated mihrab niche of its own. It has a private exit to the Hünkâr Kasrı (Royal Pavilion) built outside of the mosque. The pavilion served for both resting, waiting and working. In the Ottoman mosque architecture, the Hünkâr Kasrı was built the first time in this pavilion. Afterwards, it was added to the previously built imperial mosques.

The floor of the interior is fully covered by carpets. Therefore, the visitors are required to take off their shoes to keep the floor clean. The natural light from windows is supplemented with circular chandeliers suspended from the ceiling by chain. The small glass tulip-shaped vessels contain modern light bulbs.

Today, the magnificent structures of the Sultanahmet Mosque and the Hagia Sophia show off their beauties and the skills of their architects.

On summer evenings, there are light and sound shows at the Sultanahmet Mosque at 9:00 pm. Historical narratives are given in Turkish, English, French and German.

Due to its intense popularity as a tourist attraction, the Sultanahmet Mosque is one of the most visited mosques in Istanbul.

100 feet = 30.50 meters

100 inches = 2.54 meters

Hünkar Pavilion

Hünkar Kasrı

The Hünkar Pavilion is a special building attached to the mosque at the southeast corner. It has direct access to the hünkar mahfili (royal lodge), which is situated on the left corner of the qibla wall of the mosque in the interior. This is the first Hünkâr Pavilion built in Ottoman imperial mosque architecture. After this pavilion, hünkar pavilions were added to the other imperial mosques previously built.

Solely reserved for the sultan himself and his guests to provide security and privacy in the mosque, the L-shaped pavilion is used before and after prayer. It is a special structure designed to serve the sultan for rest in and work.

The two-story pavilion, made of stone and brick, consists of a long vaulted hall on the first floor and two rooms on the second floor. The building is entered through a ramp outside. In the vaulted hall, there is another ramp going up to the second floor.

The Hünkar Pavilion was destroyed by the big fire in 1912, and was recently rebuilt. It hosted the Vakiflar Carpet and Kilim Museum (Vakıflar Kilim ve Düz Yaygılar Müzesi) until recently.

Ahmet Vefa Çobanoğlu, (2009), “Sultanahmet Camii ve Külliyesi”, TDV Isam Ansiklopedisi. Cilt.37, p.497

Sultan Ahmed Mosque Medrese

(Religious Middle-High School) Sultanahmet Medresesi

Constructed in 1620, the Medrese is situated in the northeast corner of the Sultanahmed Mosque.

The courtyard is in the classical style bordered by a peristyle of 16 columns. There is a marble fountain at the center of the courtyard. The U-plan scheme, traditional architectural style for medreses during the Ottoman period, was used in this building. This design, first used in the medrese of Süleyman Pasha in İznik, includes rooms surround a courtyard on its three sides.

The medrese, made of stone, consists of 24 student rooms situated around a rectangular arcaded courtyard, unlike the traditional 12 or 16. Each room covered with small domes has a fireplace and two windows, opening to the courtyard and the exterior. There is also a single-domed classroom built separately on the northeast corner of the medrese. This room with a mihrab was used as mescit (small prayer hall).

The medrese system was abolished in 1924. The structure underwent renovation in 1935. During the recent restoration in 2012, a new glass roof is added to the structure creating a covered courtyard with sunlight.

Today, it is used as a depot for the Ottoman Archives.

Sultan Ahmed Sıbyan Mektebi

(Elementary School) - Sıbyan Mektebi

Sıbyan mektebi is a primary school in the Ottoman education system.

The Sıbyan Mektebi, situated in the east corner of the outer court of the Sultanahmet Mosque, was built in around 1617, the same year the mosque was built.

The square planned structure has one room. The mezzanine, built to expand the usable section, is used as a classroom. Its windows are placed in two tiers. The Sıbyan Mektebi is entered from the courtyard.

The building, used as an elementary school for centuries, stayed empty for years until its restoration. Today it is used by the Intercultural Communication Center (KIM- Kültürlerarası İletişim Merkezi Derneği), founded in 2010. The information center with its volunteers serves as a resource for visiting tourists regarding the Turkish-Islamic culture. The center’s historical and cultural presentations, free of charge, are popular among visitors.

Museum of Great Palace Mosaics

This small museum houses stunning early Byzantine mosaics, which once belonged to the northeast section of the arcaded grand courtyard of the palace.

It is the most important surviving work of Byzantine secular art, and one of the most remarkable works of the Early Byzantine period. Its technical brilliance, range of subject matter, and richness of expression mark a peak of Byzantine artistic achievement. It is without rival, the fullest post-classical expression of Greco-Roman naturalism. Portrayals are "Opus vermiculatum" (each cube is less than 4 mm) and placed in between marble pieces. The average dimension of mosaic stones is 5 mm.

The excavations, carried out at the Arasta Bazaar in the 1930’s and 1950’s, unearthed spectacularly beautiful early Byzantine mosaic pavements, as the bazaar was constructed in 1617 above the covered rubble of the Great Palace of Constantinople, built by Constantine I in the 4th century. It is believed that the palace was once extended from the Hagia Sophia and Hippodrome down to the coastline.

The mosaic belonged to a section of Peristyle Courtyard of the Great Palace. The mosaic pavements occupy three sides of a peristyle with an exterior measurement of 55.5 x 66.5 meters and a width varying between 7.2 and 10 meters. Assuming that the mosaic occupied all four sides of the courtyard, we may estimate its total area to have been approximately 1,900 square meters.(1) Although only the area of 180 m² is actually preserved, large portions of the mosaic survive virtually intact. The mosaics with an average dimension of 5 mm consist of limestone, earthenware and colored stones.

It is believed that the date of the mosaic has focused on three periods: the reigns of Justinian I (527-565), Tiberius I (578-582), and Justinian II (685-695, 705-711). All three hypotheses are consistent with the archaeological evidence. (2)

The spectacular mosaics largely feature daily life, landscapes, mythology, animals and hunting scenes. No religious themes were used. There are only three basic categories of subject matter in the mosaic, and every identifiable scene belongs to at least one of them. The categories are rural or idyllic life, animal violence, and protection.

The subjects of the mosaics are not heterogeneous. There are 4 surviving mythological scenes; 15 scenes of rural daily life; 10 hunts, or combats; 13 scenes of combat between animals; and 15 animals alone or in non-violent activities. There are also 3 scenes which combine two or more of the above elements; 8 miscellaneous scenes; and 8 scenes too fragmentary to be identified. The artist has created an analogue of human society and its relation to the natural world. (3)

This museum located next door to the Arasta Bazaar is an organizational unit of Hagia Sophia Museum.

100 feet = 30.50 meters

100 inches = 2.54 meters

James Trilling, (1989), “The Soul of the Empire: Style and Meaning in the Mosaic Pavement of the Byzantine Imperial”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Vol. 43, p 28, 30, 55

Arasta Bazaar

Arasta Çarşısı (Sipahi Çarşısı)

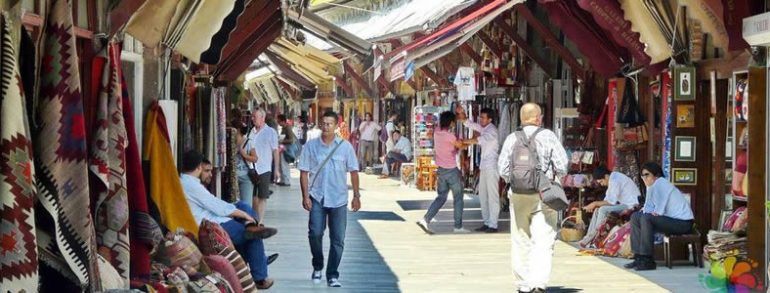

The shop-lined street consisting of around eighty stores is a part of the Sultanahmet (Blue) Mosque Complex (Külliye). Built in 1617, this historical street is also called “Sipahi Çarşısı”, as the hardware of the Sipahi (Ottoman cavalry corps) were sold here during the Ottoman period.

In Ottoman architecture, the stores of arasta, lined on both sides of a street, are made of stone and covered by a vault or roof. The arastas are specialized markets where similar products were sold. The rental income generated from the stores of arasta were used to maintain the Mosque complexes (külliye). The Egyptian Bazaar, a part of the New Mosque Complex (Yeni Cami Külliyesi) located in Eminönü, is another good example of arasta bazaars.

Due to the big fire in Sultanahmet in 1912, the bazaar, located on the Torun Sokak behind the Sultanahmet Mosque, was largely left in ruin for a long time, but it was reopened, after undergoing restoration in the 1980s.

The stores in Arasta Bazaar, which offers a flavor of the Grand Bazaar, sells traditional items, such as carpets, kilims, textiles, jewelry, handcrafts, ceramics and souvenirs.

The bazaar was constructed in 1617 above the covered rubble of the Great Palace of Constantinople, built by Constantine I in the 4thcentury. The excavations, carried out at the Arasta Bazaar in the 1930’s and 1950’s, unearthed spectacularly beautiful early Byzantine mosaic pavements dated around 5th-6th century, which once belonged to the northeast section of the arcaded grand courtyard of the Palace.

In the Arasta Bazaar, there is also a tea garden and nargile (waterpipe) cafe with a fantastic view of the Blue Mosque, where you can watch a free whirling Dervish show. This pretty Bazaar is a good low-key shopping alternative in the Sultanahmet area.

Ahmet Vefa Çobanoğlu, (2009), “Sultanahmet Camii ve Külliyesi”, TDV Isam Ansiklopedisi. Cilt.37, p.497

Nusret Cam, (1991), “Arasta, ISAM Ansiklopedisi”, Cilt 3, Istanbul, pp.335-336

Mausoleum of Sultan Ahmed I

Sultan Ahmed Türbesi

Sultan Ahmed I (1590, 1603-1617), the 14th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, died from typhus on 22 November 1617. He was only 27, when he passed away. The young sultan faced hard times, but he was fortunately able to see the completion of the Sultanahmet Mosque complex (külliye), an architectural masterpiece in Istanbul. At least, he was able to pray in his mosque.

As Sedefkâr Mehmed Agha (1540-1618), the architect of the mosque, died the following year, so, the other structures of the complex were not completed in a timely manner. The mausoleum was built in 1619 during the reign of Sultan Osman II (1618-1622), son of Sultan Ahmed I.

Situated at the northwest corner of the Sultanahmet Mosque, the mausoleum is placed in a tiny garden. It has a 12.5-m square plan, and its exterior is covered with marble. Its large and single dome has the diameter of 10.5m. (1)

The façade of the mausoleum is crowned by a triple-domed portico. It was entered from a marvelous door, made of ebony, and it was richly decorated with silver, ivory and mother-of-pearl.

The interior, extended with an eyvan in the opposite side of the entry, is decorated with impressive Kütahya tiles and painting. Similar to the interior of the mosque, the walls until the second tier windows are covered with beautiful tiles, and the area above it has magnificent paintings. It receives the daylight from its 52 windows in three rows.

Today, the mausoleum of the Sultanahmet Mosque is a permanent resting place for Sultan Ahmet I, himself, together with his wife, Kösem Sultan, their two sons, Murad IV and Osman II and other descendants. There are 36 tombs in the mausoleum.

Ahmet Vefa Çobanoğlu, (2009), “Sultanahmet Camii ve Külliyesi”, TDV Isam Ansiklopedisi. Cilt.37, p.497

Behçet ÜNSAL, “İstanbul Türbeleri Üzerinde Stil Araştırması”

Godfrey Goodwin, (2003), “A History of Ottoman Architecture”, Thames & Hudson Ltd London, pp342-343.

A. Ihsan Toksü