Carpet

When archeologists discovered the Kurgan tombs in Pazyryk Valley in the Altay Mountains in East-Central Asia during excavations in 1947-49, they did not expect to unearth a Turkish carpet used by horse-riding pastoral nomads of the steppe. Presently known as the Pazyryk carpet, belonging to the 4th-3rd century BC, today, it is the oldest ever known knotted carpet, currently displayed at St. Petersburg Hermitage Museum.

Carpets are downy and knotted fabrics. Unlike the Persian knots, Turkish knots have double warp, therefore, are more durable, and are more suitable for weaving geometric patterns.

After a long gap, Anatolian Seljuk Turks introduced their carpet masterpieces in 13th century AD, which is considered their first best period. In his diary, Marco Polo (1254-1324), the Venetian merchant traveler, mentioned fine carpets woven in Konya, Beyşehir, Aksaray and Sivas in central Anatolia. With a perfect harmony, they used few colors, but they were skilled at finding the perfect harmony between the lighter and darker colors. Main colors were red and blue, yellow and green were seldom used.

The most characteristic feature of the 13th century Seljuk carpets are their borders, Kufic script, and geometric motifs. After the second half of the 14th century, animal figures on the Anatolian carpets became more popular, as Seljuks lost their power.

The second best period of the Anatolian carpets was the 16th and 17th century when the Seljuk carpets were replaced by the magnificent Ottoman palace and Uşak carpets in western Anatolia. They had popular appeal with rich Europeans.

Palace carpets were woven at the workshops of the palace, where they used silk, wool and cotton. Unlike the Anatolian carpets, they were woven in the Persian knot (single knot). Spring flowers, garden plants and small medallions are commonly used patterns. Designs were created at the design workshops (nakkaşhane).

Europeans’ attention was directed at the Turkish carpets in 1891 when an important exhibition of oriental carpets was held in Vienna. Wealthy individuals and museums started to build their collections with old carpets. After 1900, the bourgeois class rushed to buy new carpets. This affected the quality of the newly woven carpets. The carpets, produced before 1870, are classified as antique.

Kilim (Rug)

Kilims are flat, unknotted and hand-woven textiles. Unlike the carpets, kilims are woven using vertical warps (length) and horizontal wefts (width) to weave the threads together. Usually the warp is made of wool, and the weft of wool or cotton. The difference between the front and back is very slight.

Kilim, a word of Turkish origin, is one of the best examples of Turkish folk art, and was commonly produced and used by tribes. They are named according to their tribes, motifs and colors. Geometrical patterns representing life, beliefs, animals and plants were best suitable for kilim weaving technique, which stayed unchanged since the Seljuks. The oldest pieces of kilims with the figures of men and women, woven by Turks, were discovered during the Noin Ula excavations in North Mongolia.

Motifs, as the Mode of Communications

Without knowing the tradition, culture and heritage, no one can fully appreciate the carpet or kilim. They are beyond being a piece of the beautiful furniture decorating your home. Having a carpet or kilim at home, in fact, is like having a piece of abstract art reflecting a brief history of an Anatolian native’s life, which might be happy or sad, lucky or longing, loving or tearful. For centuries, kilims have been produced and used by women to express their feelings. Women weaving kilims for their dowry chests use this way of communication to express their hopes. Those women may not be well educated in today’s norms, but they have a culturally inherited knowledge of the language of kilim. Therefore, carpets and kilims are exclusive products transmitting valuable messages from the depths of history in Central Asia to the present time in Anatolia.

Carpets or Kilims are cultural and psychological chronicles of the society. Therefore, the motifs on the kilims should be deciphered to appreciate them fully.

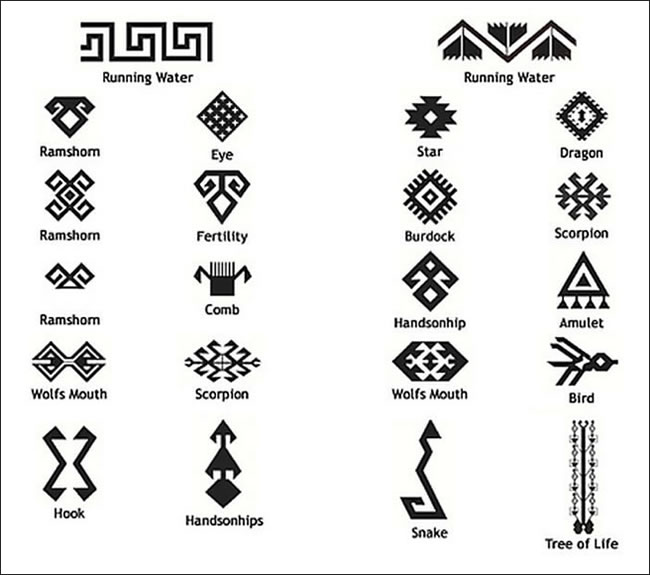

Most common motifs can be characterized into four groups:

1. Life and protection; hands-on-hips, ram’s horn, hairbands, fertility, earrings, combs, stars, waterlines, evil eyes.

2. Beliefs; amulets, crosses, hands, hooks.

3. Animals; birds, dragons, scorpions, snakes.

4. Plants; burdocks, trees of life.

Hands-on-hips, representing motherhood and fertility, is often used when the proud weaver gives birth to a boy. Ram’s horn signifies men’s power, fertility, heroism and productivity. Hairbands and earrings show the weaver’s desires to marry. Waterlines, or running water, represents life. In Anatolian culture, water means life. Evil eye and hook are used as protection. Hooks are also used as a connection between male and female motifs.

Since a serpent offered Eve the forbidden fruit, snakes were used in art as a symbol. In kilims, it denotes happiness and fertility. The weaver wants to have the power of a scorpion’s fatal venom to protect herself or her family. The tree of life represents immortality and a hope for the life after death. The cypress tree is widely used on Anatolian kilims.

Ayla Ersoy, (2008), “Traditional Turkish Arts”, Republic of Turkey Ministry of Culture and Tourism publication, pp.55-81

Nurdan Taşkıran, “Reading Motifs on Kilims: A Semiological Approach to Symbolic Meaning”

Nirnaz Er, (2012). “Bir İletişim Aracı Olarak El Sanatları”, Batman University, Turkey.

Selman Kardeşlik, (2010), “İstanbul Vakıflar Halı Müzesinde Konservasyon Çalışmaları ve Yeni Keşfedilen Selçuklu Halıları”, Vakıflar Restorasyon Yıllığı, Yıl: 2010, Sayı: 1

Ulrich Schürmann, (1966), “Oriental Carpets”