Medrese (or madrasah), meaning “the place where lessons are given”, is a secondary or high school in Islamic countries.

The first reference to medreses was the house in Medina where the Koran was taught. The house was called dârülkurrâ. The real medrese was opened in Nishabur in the Khorasan Province of Iran in 954, called dârüssünne.

Medreses were developed by the Seljuk Turks. Seljuks opened the first medreses in Anatolia early on. Tuğrul Bey of the Seljuks opened the first medrese in 1046. These medreses were financially supported by the foundations (Vakıf). Medreses started specializing in this period. Medreses were built by state dignitaries and wealthy people. Sivas Gök Medrese (1271) and Sivas Çifte Minareli Medrese (1271) are among the surviving Seljuk medreses.

The medrese system continued during the Ottoman Empire. Orhan Gazi opened the first Ottoman medrese, İznik Medresesi, in 1331 in Iznik, which still remains. When Sultan Mehmed II conquered Istanbul in 1453, the education center of the empire moved to Istanbul from Edirne where the leading school was the Üç Şerefeli Mosque.

Mehmed II converted the Monastery of Christ Pantocrator into a Medrese for a while. It was named after Molla Zeyrek, a religious scholar. He opened another medrese in Hagia Sophia. The first medrese in Istanbul was the Eyüp Medresesi opened by Mehmed II in 1459. The Fatih Külliyesi, a mosque complex built in 1470 by Mehmed II, had eight medreses, called Sahn-ı Seman, today the equivalent of a university and a research center.

The Süleymaniye Medresesi, established by the Sultan Süleyman in 1557, provided the army with medical practitioners and engineers. The school also had a branch (Dârül Hadis) for a graduate program in theology.

According to the chronicles of Istanbul, 350 Ottoman medreses were built in Anatolia and Rumelia between the 14th and 16thcenturies. Throughout the history of the Ottoman Empire, 665 medreses were established in Rumelia (the empire’s European province).

In the Ottoman education system, the most important thing was not the school itself. Instead, they valued the professor the most. From religion and philosophy, to math and engineering, there was a very wide scope of subjects offered in the medreses. Textbooks were in Arabic, but Turkish was spoken in the classroom. There were classes every day, except on Tuesday and Friday. Only boys who were literate and graduated from “sıbyan mektebi” were accepted to the medreses, boarding schools at that time. Students at the high school level were called “softa”. They were called “danişmend” in the university level. Students sat on pillows on the floor during lessons.

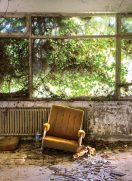

The medrese buildings, made of stone, usually had one-story, and domed classrooms situated around a courtyard. Most of the Ottoman medreses were built in U-plan design, in which the rooms surround a courtyard on three sides.

Most of the külliyes (architectural complexes) built during the Ottoman Empire included medreses in their complexes.

Imperial külliyes provided the highest education. Among the well-known medreses were Fatih Medresesi, Süleymaniye Medresesi and Sultanahmet Medresesi.

In the late 18th century, engineering branches were separated from medrese systems. After the beginning of the 19th century and on, medical, legal and political branches were excluded, and only religious studies were left to the medreses. These changes caused the medrese system to lose their financial privileges.

Medreses were closed on March 3, 1924 and all the schools were transferred to the Ministry of Education.

Ekmeleddin İhsanoğlu, (2009), “education, the Enciclopedia of the Ottoman Empire”, by Gábor Ágoston and Bruce Masters, pp. 198-204

Ersoy Taşdemirci, “Medreselerin Doğuşu Kaynakları ve İlk Zamanları”, Erciyes Universitesi

Mehmet İpşirli, (2003), “Medrese, Osmanlı Dönemi.”, TDV, ISAM Ansiklopedisi. cilt 28, p.327

Mustafa Şanal, “Osmanli Devletinde Medreselerdeki Ders Programlari”, Erciyes Universitesi

Zeynep Ahunbay, (2000), “Ottoman Medreses, Ottoman Culture and Arts” ITU, Istanbul